As a child, I learned that I could “read” objects. I learned this by accident and in a rather traumatizing fashion. But that is a story for another time. Another night.

It’s always at night that I get called.

“I have been in a lot of dark places over the years; some lacking in light, some devoid of hope. Some were both.” That’s from a book called Odd Thomas, that my English teacher made us read in 9th grade. That guy (the teacher) said he didn’t really believe in supernatural mumbo-jumbo. By that age—much like the hero in that story—I knew better than to demonstrate any such thing in front of anyone except my closest friends.

It was one of those friends who had called me out to this small ranch house on a slightly overgrown lot on the outskirts of town. ‘End 35 Speed Zone’ said the sign. a dozen yards past the driveway. The streetlights ended just past the sign.

People who have read Harry Potter books think that mine would be a “cool” ability to have. I don’t think so myself, because, for starters, I have to put on gloves as soon as I leave the safety of my battered old Honda. This is only the end of September, and no one is wearing gloves yet—except me.

Since vinyl or latex “safety” gloves tear too easily, I favor thick wool ones that I get in bulk from an Army surplus store. They are made in a factory and boxed by a machine, and therefore lose most of their original ‘memory’ before they get to me. Not that sheep have many thoughts or experiences that might disturb me in the first place. Occasionally I get a glimpse of the surplus store owner’s wife, if she has counted the number of gloves in the box.

She seems like a nice lady, albeit one who has what some might consider an unusual and possibly unhealthy level of obsession with LL Cool J, currently star of some cop show on TV. I don’t watch cop shows, as I get too much of that in real life.

The case was a kidnapping, one that hadn’t made the news yet, because so far Tim was the only one who knew about it. He had to call me before he called the state police and the FBI, because I didn’t have a badge and wouldn’t be welcomed at a crime scene by anyone except him.

We didn’t speak as he met me at the garage door, or as he gave me a pair of slip-on hospital booties to cover my shoes. We continued wordlessly as he led me through the kitchen toward one of the bedrooms. He had learned to be careful about prejudicing my thoughts, and I was careful not to touch anything, even with my gloves on. I managed not to puke when passing the feet of a small woman, sticking out of the bathroom. I could smell the blood from in the hallway—fresh.

I admitted to myself I was glad the body was not the main attraction. But my nausea deepened as I followed Tim further into the house, wondering what could possibly be worse, why he had called me.

Reaching the room in question, I paused before entering. Took a deep, centering breath. Then I scanned the interior, trying to get as much as I could with my eyes before I opened up to all the extra.

It was done as a child’s bedroom, a young girl. But it wasn’t right. The wallpaper had some kind of farm theme, but it was peeling in places, and the plant on a delicate corner table near the window was an aloe plant—half dead—with spiked leaves, unsuited to a little person’s space. Everything else, all the toys on the shelves, the books, the bedding, all of it was too new, too complete, too perfect, too orderly, and most of it looked unused. Even with my gloves on, I knew I would not find a little girl’s imprint on most (if any) of the objects in the room. It was staged.

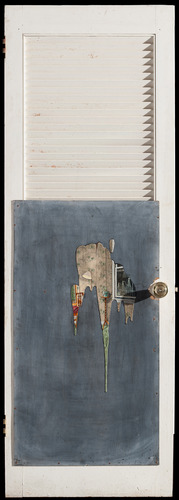

A closet in the back corner was open. Tim didn’t need to lead me to it, it was, I already knew, the only interesting thing in the room. The door, when new, had had a thick coat of white paint, matching trim around the baseboards, all of it now dingy. The main portion was crossed with functional slats commonly called louvers. I had to look up the spelling. Still don’t know why closet doors of a certain era are ventilated—what’s the point? A few slats at the bottom were broken and loose, looking as though they had been attacked from the inside.

The back of the door—that is, the inside of the closet—had been repaired ad hoc with some cheap particle board, all down the lower half . This had been done by someone apparently lacking any tool other than a hammer, as the piece had been nailed in…with a “cutout” for the door handle that seemed to have been merely bashed out in chunks with some blunt instrument, rather than sawn or drilled.

There was a lock on the door handle, which did not look original, and in fact the side for the key was facing the wrong way—into the closet. Who bothers to put a lock on a closet door? And why would you need to lock your stuff IN? As if the woman’s corpse wasn’t bad enough, I was already getting a bad feeling about this.

In the closet was a row of men’s shirts, size large, a complete contradiction to the rest of the room. Nothing that looked expensive, mostly solid colors, but some that had stripes or a small checked pattern. Nothing trendy or new, all showing signs of wear around the collars and cuffs. Tim used a small flashlight to spotlight a long dark hair that clung to the cuff of one shirt, near the middle of the row. I removed my left glove and got ready for the jolt I knew was coming. Running just a fingertip along the hair, I saw her.

She was perhaps eight or nine years old. That long dark hair, not black, but a chestnut shade of brown, came from her head. She was crouching in near-darkness, staring at the upper slats of the door. From this angle, looking right into my face.

I shuddered, and then broke the silence for Tim. “A pink t-shirt with a black-line pony on it. Dark jeans.”

He tapped this description into his smart phone. “Is she alive?”

I put two fingers on the shirt cuff.

She was singing to herself, but stopped when the doorknob clicked, then opened. She cried out, a brief sound that wasn’t loud, but nonetheless caused my own throat to choke up in the residue of her pure, uncut fear. A man, large, looming, his face backlit and hard to see. But it was Uncle Mike, this was his house, she could see the funny wallpaper between his legs. He held out a hooded sweatshirt, and told her to put it on. She stood up, and felt woozy. It was hard to put her arms into the hoodie sleeves.

I couldn’t take any more, let go of the fabric.

Tim started to ask again, but I cut him off. “Yes--or at least she was when she left this spot.”

“Amber Alert just went out across the state.” Holding up his phone to show me, he did his best to keep a calm voice, though I had known him long enough to hear the hard edge in it.

“Tim, what is this mess? What have you gotten me into?” I whined.

He stared at me. “Could you try the bodies?”

“Plural? WHAT THE F---, Tim? More than one?” I was losing whatever composure I’d had.

“There’s…Jesus, I’m sorry, man.” The edge was replaced with some sympathy for me, the non-cop, who had not signed up for this.

“There’s no other way to say it. Little boy in the bathroom too. Think it’s her brother. You have to be quick, the staties and Feebs are on their way.”

“I am NOT touching the dead body of a child, Tim. No, no, no, no, nooooo sir.”

“How about the mother’s shoe? No direct contact?” His voice was calm, but his eyes pleaded.

I walked back into the hallway and took a knee outside the bathroom door so that I couldn’t see inside. I touched the heel of the loose shoe, half off her foot. I felt the shock of the blow as a faint tremor in my hand, same face, with a weapon raised overhead.

“Was it Uncle Mike?”

“Yes.” I put my glove back on and immediately retraced my steps out of that place. I don’t remember the drive home.

…

Inspired in part by the work of Dean Koontz, obviously; but also Mr. Tuttle's art, and partly by the events of the real-life Hannah Anderson abduction. Remember kids, truth is always stranger than fiction.